Peace Family.

I was recently asked why is KAMTA and the maa aankh so important to me? It was a loaded question.

So, I began by stating that it was Brother Arthur Flower’s Hoodooway list (which I had the honor and priviliege of participating on) and the Orb of Djenra blog that first brought to my attention that although early African Americans weren’t able to preserve a large portion of their religious culture as their kin had done in the Caribbean and Latin America. Early African Americans did manage to preserve a great deal of it through dances, folk practices, proverbs, songs and history. It was through these various cultural practices that early African Americans were able to preserve their cultural way by passing on traditions, which became the basis of African American shaman tradition known today as Hoodoo or Rootwork, as it was called in the northern states where I am from.

Contrary to popular belief, Hoodoo/Rootwork has never been all about casting spells for ill, doing magical work and making pacts with the devil. This is all sensational nonsense that was created years ago by racist individuals and promoted through a stereotypical media that took advantage of the public’s ignorance about people of African descent. Unknown to most Hoodoo/Rootwork is an African American folk practice that was created by African Christians during slavery. Like most folk practices such as the European folk practice of reading of the Psalms, praying and saying grace before a meal, the use of sacred objects like blessed oil, blessed water, the Holy Bible and so on. Hoodoo/Rootwork in employed to obtain spiritual and often divine remedies for material and physical ailments such as problems with money, obtaining love, protection from evil and so on. Hoodoo/Rootwork as you can see is very similar to European folk practices. The only difference between the two is that the African American folk practice was created and used by African slaves in order to fight, resist and struggle against the cruelties of slavery.

Contrary to popular belief, Hoodoo/Rootwork has never been all about casting spells for ill, doing magical work and making pacts with the devil. This is all sensational nonsense that was created years ago by racist individuals and promoted through a stereotypical media that took advantage of the public’s ignorance about people of African descent. Unknown to most Hoodoo/Rootwork is an African American folk practice that was created by African Christians during slavery. Like most folk practices such as the European folk practice of reading of the Psalms, praying and saying grace before a meal, the use of sacred objects like blessed oil, blessed water, the Holy Bible and so on. Hoodoo/Rootwork in employed to obtain spiritual and often divine remedies for material and physical ailments such as problems with money, obtaining love, protection from evil and so on. Hoodoo/Rootwork as you can see is very similar to European folk practices. The only difference between the two is that the African American folk practice was created and used by African slaves in order to fight, resist and struggle against the cruelties of slavery.

It was through this folk tradition that the shamanistic practices brought from Africa were able to survive the tragic slave experience and contribute greatly to African American spirituality. As a result, early African Americans were able to continue to mark very important events that occurred in his or her life through a spiritual blueprint or cosmogram called the Kongo Cross.

It was through this folk tradition that the shamanistic practices brought from Africa were able to survive the tragic slave experience and contribute greatly to African American spirituality. As a result, early African Americans were able to continue to mark very important events that occurred in his or her life through a spiritual blueprint or cosmogram called the Kongo Cross.

As I mention in MAA AANKH Vol. 1, I first learned of the Kongo Cross through my deceased grandparents. One day while contemplating how to do something that I remembered my grandparents use to do. Shortly after, my attention was drawn to my grandmother’s obituary notice and there it listed her birthday and the day she died, but most African Americans have a strong ingrained cultural taboo against saying death or that someone died, especially when the individual was a godly-minded individual. Instead most African Americans say that the person “passed” or “passed away”, because although physically they do not exist something within our psyche knows that their soul continues to exist. On my grandmother’s obituary instead of saying like I have seen on other cultures obituary birth and death date, it stated Sunrise and Sunset.

This was amazing to me because I had, had this obituary for the longest time and looked at it numerous times and never saw that. I could’ve called it mere coincidence that I was thinking about doing something that drew my attention to look at my grandmother’s obituary notice. I could if I was arrogant, naïve and didn’t believe in spiritual (invisible, non-material) intercession, but I do, which is how I “humbly” came to realize that ancestral spirits do exist. It was proof that the righteous souls do continue to exist and do not die. In other words, there is “life after death”; these ancestral beings just continually to exist as spirits.

This is how I truly learned about the Kongo Cross and came to really understand African American spirituality. It was this understanding that led me to see that the Kongo Cosmogram besides marking one’s birthday and their death. Also signified other important events like the initiation into African American fraternities and sororities, as well as significant spiritual events like the day an individual was baptized, came to God or converted to their chosen religious faith. It was all a reminder of one of the things older African Americans were known for saying, which is, “That we all have to go through something, in order to get something.” This something I later discovered as I analyzed my life helped me to see that life is all about the choices that we make. It made me realize that many of our choices are ill-informed choices and unwise decisions. Some of us continue to keep making these same choices, which lead us into the same unproductive relationships, same unwise money purchases, etc. All because someone never told us that this is our life and it is up to us to make the best out of it. This means that just like everything else we have to learn how to make better decisions, which means learn from the past (your past and the past of others-ancestors-history).

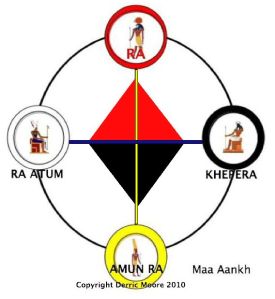

This is one of the most valuable lessons that I learned from the Kongo Cross, which led to the creation of the maa aankh, a cosmogram inspired by the Kongo Cross but based upon the Kamitic/Kemetic (Ancient Egyptian) concepts and principles. It was through the maa aankh it became apparent that when we learn from our mistakes, face our fears, and overcome our faults, that our spiritual talents are activated. This is our initiation system where we become great healers, musicians, entertainers, speakers, politicians, etc. There are countless stories of African Americans that have had this spiritual awakening. This is why most grown people don’t particular care for teen boppers singing about love because deep down we know that this 15 to 24 years old doesn’t have any real experience with the subject matter. The older folks use to say, “They don’t have any SOUL”. Before then, it was called in our churches ANOINTING.

When you have ANOINTING, it is truly a powerful, cultural experience that can’t be explained in words because it is a mystical connection between you and the Divine. It is similar to an assurance that everything is going to work out but it is also a pledge that you have to do your part.

It is for these reasons I can truly say that the maa aankh is not a New Age, magical circle creation based upon syncretic beliefs with sacred technology. It is truly an initiation system that has been handed down to us from the first Africans brought to North America. The early African Americans just never called it an initiation/spiritual system or “religion” because like most indigenous people. They didn’t regard their spiritual beliefs and practices as a “religion” in the way religion is viewed today as a set of beliefs and practices only performed one or a couple of days out of the week. No, their spiritual beliefs and practices were an integral and seamless part of their way of life. It is this understanding of the maa aankh that makes it so special to me, because it helped me to move beyond intellectualizing about being religious and spiritual, to actually Being

It is from this understanding that I have been informed to refer to this African American cross-spiritual practice as Kamitic/Kemetic shamanism because it offers various forms of healing including giving one a sense of purpose and access to forgotten knowledge (traditions). This is accomplished by entering into an altered mind state or a meditative/mediumistic state of mind, similar to dreaming, except one obtains information and power that can help them in their physical life. It works because it has always been a part of the plan for us to seek and connect with the Divine within our being in order to succeed in life.

I am aware that there are other Kamitic/Kemetic initiation systems that exist and I applaud the creators and founders of those systems, because they assisted me in realizing my divinity, as well. But the maa aankh is truly dear to me for several reasons. The first is because it was derived from my most recent ancestors (my grandparents and great grandparents). Second, since the maa aankh was derived from the Kongo Cross, which was created by the Kongo-Angolan people, a Bantu ethnic group, through it I was able to get a glimpse of my ancestral past. Last but not least, since the maa aankh also helped me to stretch back into time and get a glimpse of my Bantu ancestral memories, I was able to imagine and thus reconnect to those Bantu people that walked alongside the Nile River. There simply is no greater joy than being able to reconnect to the Divine through your ancestral, cultural heritage, because once that connection is made there are unlimited possibilities as to how it can be expressed. Another great advantage is that suddenly your small, limitless world all of sudden expands as you sense the cultural connection between you and others. Everything takes on a new meaning not because you intellectualize it but, because you see the spiritual significance of it. Like Capoeira before I saw it as a beautiful Afro-Brazilian art, but after my experience I see it as totally integral with my way of life. When I do play in a a roda, I found myself easily going into the au (cartwheel) to access power or axe’ (ashe) from below (within, from the ancestors, etc. however you want to look at it). Dancing rather it be to Mary Mary’s God in Me, Machel Montano’s Too Young to Soca, Bob Marley’s Soul Shake Down Party, Holwin Wolf Smokestack Lightnin to Celena Gonzalez’ Santa Barbara or Bamboleo’s Tecapacita. It all has new meaning because even dancing helps to propel into the mystical realm some refer to as Zen. It is all part of the awakening experience where one is blessed, and his or her talents are awakened, as they feel the Spirit, hence ANOINTING.

Simply put, it is a spiritual system that acknowledges our divinity because it is based upon our biological and cultural identity/self.

Amun Ra

Amun Ra

For more information see MAA AANKH: Finding God the Afro-American Spiritual Way,

by Honoring the Ancestors and Guardian Spirits by Derric Moore

Copyright 2010 Land of Kam

Reblogged this on sheila mbele-khama.

Reblogged this on afro-Fusionist abstratz.