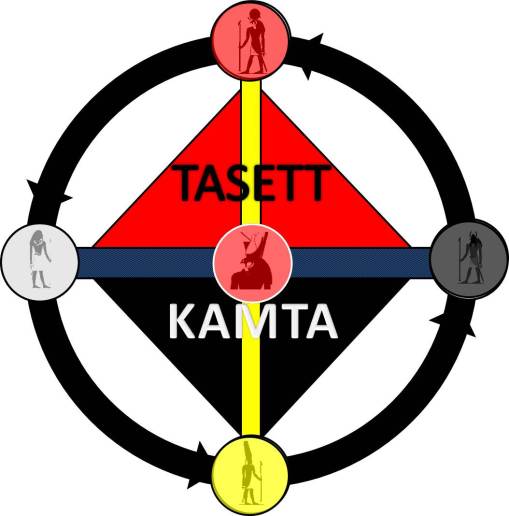

What is Kamta?

Kamta is the spiritual tradition of my ancestors and spirit guides, whose spirituality initially had no name. The origins of Kamta are inspired by the Black Experience in North America. Due to the successful slave revolt on the island of Hispaniola, which resulted in Haitian independence,. African American spirituality was suppressed and demonized throughout the western world, especially in North America, out of fear that another spirit-led revolt could occur. According to Albert Raboteau, author of Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South, if slave owners caught early African Americans praying or engaging in any spiritual practice outside of their highly supervised church, they could be severely beaten, dismembered, or even killed. Therefore, to plead with God, to preserve the fragments of their African culture that they could remember, and plot insurrections, early African Americans held secret meetings in hush harbors, which were fields, ravines, swamps, or heavily wooded areas that would make the sounds of the enslaved’s worship inaudible to the slaveowners nearby.

Although, many historians believe that the enslaved Africans and early African Americans created their own version of Christianity on American soil, and that they fled to practice their own version of Christianity, the facts are that prior to the advent of the transatlantic Slave trade, the Kongo king Nzinga a Nkuwu converted to Christianity around 1491. His son, King Afonso Mvemba a Nzinga, made Christianity the official religion of the Kongo kingdom around 1509. Therefore, most of the Africans shipped to the Americas from the Kongo-Angolan region, such as the “2o and odd” Angolans that arrived at the British settlement, in Jamestown on August 20, 1619, were either Christian or familiar with the Christian faith. Consequently, the enslaved Africans and their descendants were aware of the Baptist principles long before there was a Baptist denomination, according to Dr. Wayne E. Croft (A History of the Black Baptist Church: I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired, p. 195.).

IT'S NOT HOODOO it was CONJURE & ROOTWORK

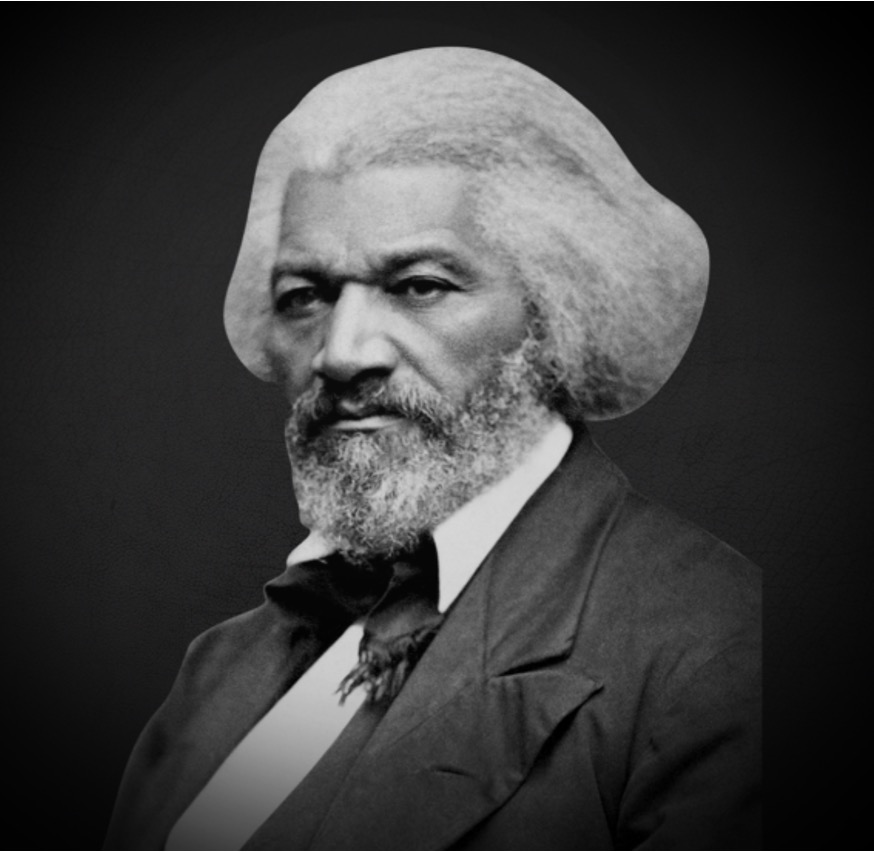

People forget that in Frederick Douglass’ autobiography, he recounts that when he was a young man, he attempted to run away from the farm he was enslaved on. Douglass states that while hiding in the woods, because he was tired of the cold, and hungry, he had no choice but to return. While in the woods, he encountered Sandy Jenkins, who was a genuine African conjurer, as Douglas puts it, who practiced a religion “that had no name.” Douglass said that Jenkins gave him a root and told him that no white man would beat him again. When Douglas returned to the farm, he said that Mr. Covey, the slave breaker, passed him by and he was really cordial, which Douglass wondered if he was behaving this way because it was Sunday or the root. Then, Douglas stated that on the following day, he and Mr. Covey got into it, and Douglass fought his abuser and drew blood. Douglas states that was the day “the slave became a man.”

From Douglass’ account, the Slave Religion was different from the religion that the enslaved African Americans were taught.

Douglass also shares the sentiments that most enslaved African descendants in North America shared, which he wrote in the appendix of his 1845 book, where he wrote:

“I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land. Indeed, I can see no reason, but the most deceitful one, for calling the religion of this land Christianity. I look upon it as the climax of all misnomers, the boldest of all frauds, and the grossest of all libels…”

So, enslaved African Americans would flee into the night so that they could worship freely and in secret their version of Christianity.

After slavery was emancipated and time progressed, many African Americans became more influenced by Western Christian ideology and less influenced by African religion. However, some African Americans continued to cling on to the old ways. Instead of meeting in secret in the fields, ravines, swamps, and heavily wooded areas,. They had a prayer room, a prayer closet, or a prayer warrior room because our Ancestors’ religion was Conjure & Rootwork.

What's the difference between Conjure & Rootwork and Hoodoo?

Although some may disagree, the difference I have found is that Conjure & Rootwork have religious and spiritual overtones that guide the actions and behaviors of the practitioner. Whereas hoodoo is just a magical practice or witchcraft where the religious aspect is optional. Conjure & Rootwork were practiced by most preachers and the elders in the church. They didn’t call it a name because each person’s C&R was different. One of the most famous C&R preachers was Bishop C. H. Mason.

In the video to the right, Erika Alexander, the famous actress best known for her role in the hit comedy series Living Single, unknowingly confirms the difference.

My Path, Mi Manera, My Maa, My Truth

I did not discover Kamta, Kamta discovered or chose me. You see, I was born and raised in an Apostolic Pentecostal “Jesus-only” home. My father was a preacher/pastor, and my mother was a Christian songstress. My parents were not as strict as a lot of other parents I have heard of, like my grandparents, who didn’t believe in watching movies, watching TV, reading certain books, etc., because they thought that they were protecting their souls from the devil. My parents were somewhat in the middle because they were the descendants of the parents of the Great Migration (1910–1971). However, my family attended church six times a week, and sometimes more if we visited different churches in the City of Detroit or there was a State convention.

I had a relatively good and safe childhood, which I learned as I got older because of some spiritual protections that were put in place to safeguard my siblings and me. As a child, I never noticed these things, and I never asked because the cultural norm back then was that ‘children are to be seen and not heard.’ But when I got much older and met my first spirit guide, I recall that my parents, grandparents, great aunts, and uncles were former Baptists who were now Apostolic Pentecostals, or COGIC, from Memphis, Tennessee, which is one of the main hubs that had a strong Conjure tradition with a heavy Congo influence that cultural anthropologist Tony Kail writes about in his book A Secret History of Memphis Hoodoo. As a result, I never saw my relatives light a candle for anything, but they used blessed olive oil, herbed-infused olive oil, and blessed water for everything. At many of the visiting churches we would attend, some of the practitioners used blessed candles and the like. I remember people would seek the assistance of some of the elders in the church because of their ability to pray away illness, change situations with prayer, and cast out demons. Now, I do recall hearing the word roots on the radio, asking my mother what it was, and being told it was something that evil people did, but I never heard the word hoodoo.

I later learned that it was my ancestors and spirit guides who encouraged and inspired me to read and learn about the Ancient Egyptian or Kemetic religion, but because African spirituality and traditions were suppressed and demonized, coupled with Christianity’s belief in good versus evil, I didn’t know about spirits or spirit guides. I didn’t know about psychic or spiritual abilities, and spiritual tools. So, I spent a lot of time reading and studying the Kemetic religion, traditional African and other world religions, African and Eastern philosophy, metaphysics, etc.

I studied alone and under the tutelage of others, which led me to meet some very unscrupulous individuals as well as some very honorable followers in various Afro-Diasporic traditions, like the Conjure woman Ms. Smith and Ms. B, a palera (Palo priestess). However, the most influential individual I met was my mentor, Papa, an elderly Afro-Cuban man who was Babalawo in Lukumi, an Espiritismo Cruzado practitioner, and a member of the all-male Abakuá Society.

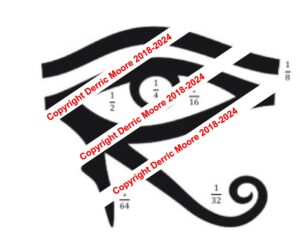

Papa taught me a lot about working with my ancestors and spirit guides. Later, I met a priestess of Oshun, who informed me that my incarnation was overseen by Djahuti (Thoth, Hermes), and that I was called to be a shaman. I was reminded that Djahuti repaired Hru’s (Horus) eye, which allowed Hru to defeat his evil uncle Set. She further explained that the reason I was having all these problems or tests (la pruebas) was because I refused to answer my Calling.

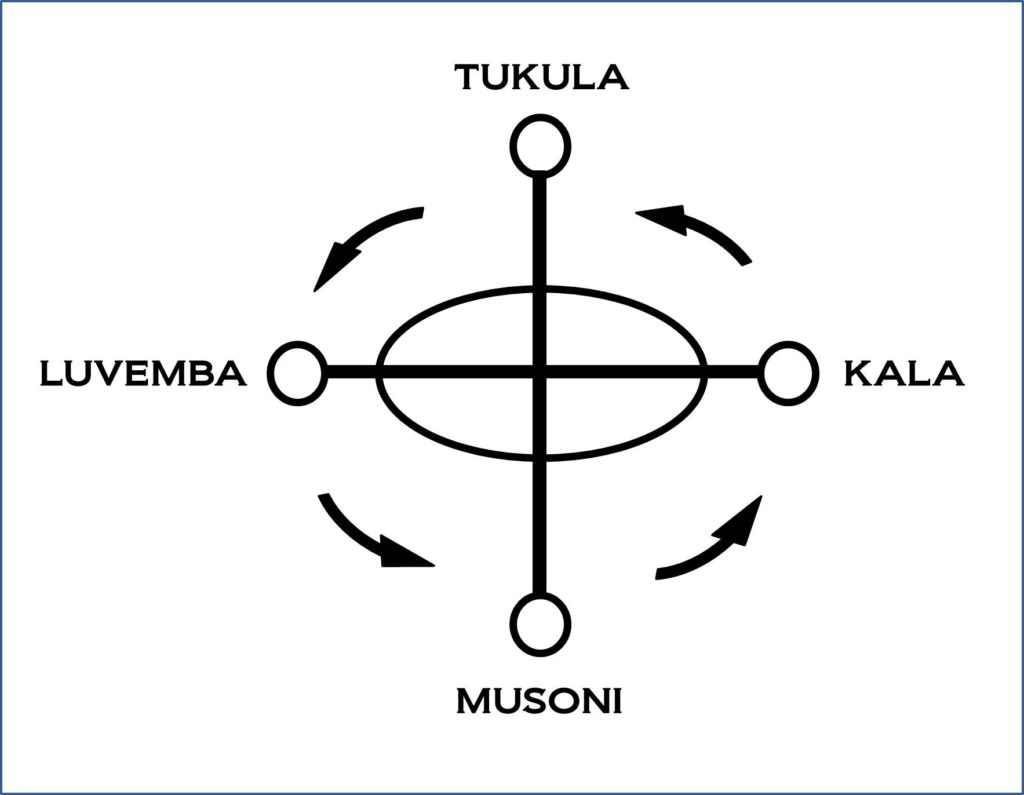

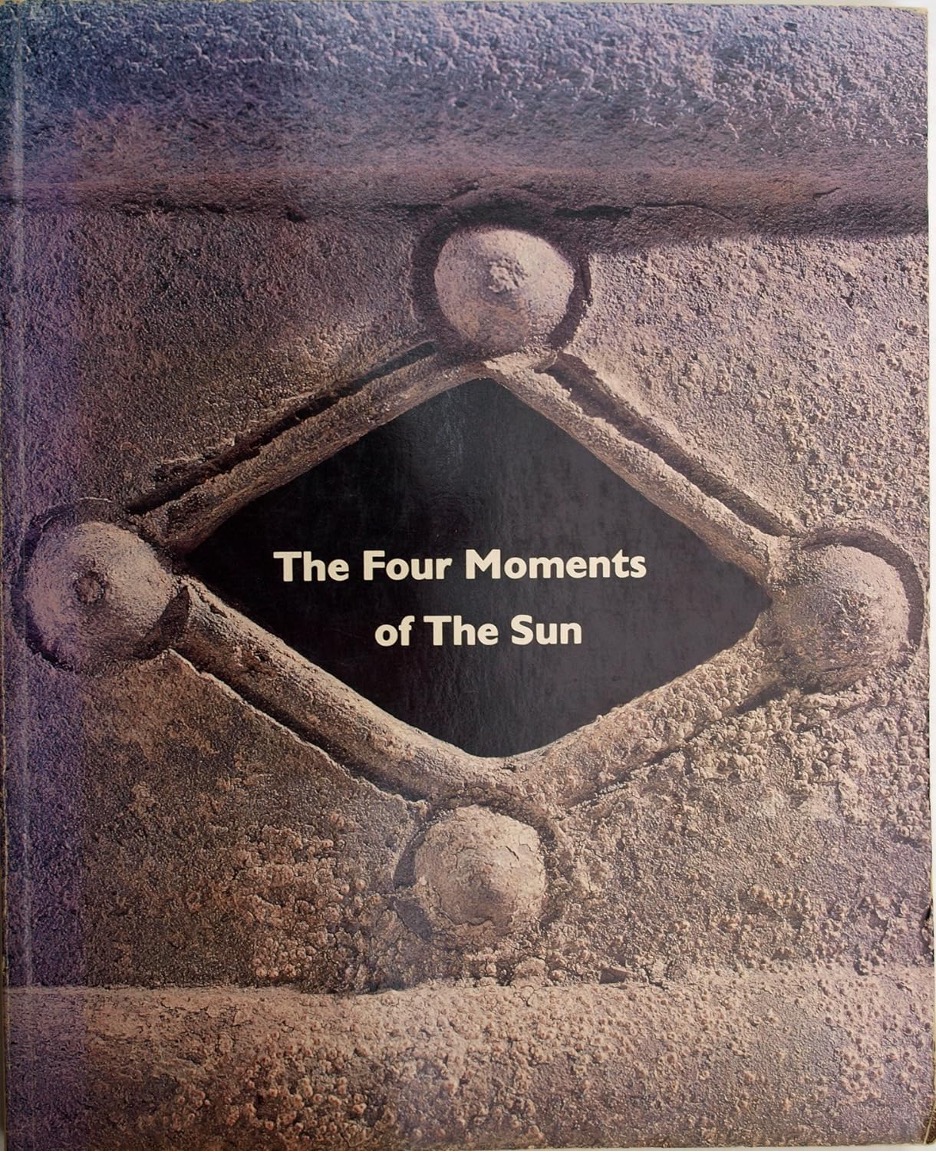

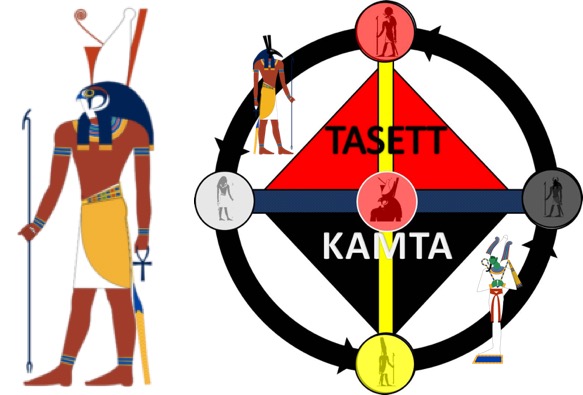

It was long afterwards that I became deathly ill or had a shamanic illness. Upon my recovery, I went through a type of purge where everything that did not serve me was removed from my awareness. As a result, it was through my ancestors and spirit guides that I read (studied) Farris’ The Four Moments of the Sun and learned about the Kongo cosmogram, which led me to discover the Maa Aankh cosmogram.

Since my ancestor tradition had no name, other than being called Conjure and Rootwork, my ancestors and guides advised that I call this tradition Kamta since this is where my ancestors reside.

Kamta is a shamanic spiritual tradition that heavily draws from the Ancient Egyptian or Kemetic theology, the remnants of the Bantu-Kongo philosophy that survived through slavery in North America, combined with African American folk beliefs and practices, and Espiritismo Cruzado (also known as Afro-Cuban Crossed Spiritism). Kamta is not a reconstruction tradition that is focused on reviving the Kemetic tradition of old, but is a practical tradition that places emphasis on communicating with the Ancestors, and connecting with nature to achieve and maintain balance, or Maa (Divine Balance, Absolute Truth, etc.).